The geospatial community , for many years now, has articulated the role and value of geospatial information for governance. With the UN’s Sustainable Development Agenda fresh off the block, now is the moment where it should elevate and demonstrate the geospatial value proposition.

The United Nations ’ Millennium Development Goals ( MDGs ) initiated in 2000 made significant progress in a number of areas of sustainable development . However, the progress remains uneven, particularly in the least developed and developing countries . Also, many of the MDGs were never fully realized, in particular those related to maternal, newborn, child and reproductive health.

To continue the development strides and to fulfil the vision of MDGs , the United Nations announced the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development in September 2015 — an ambitious, integrated, indivisible and transformational global agenda to reach the ‘furthest behind first’. The 17 Sustainable Development Goals, 169 associated targets with 230 indicators, promise to achieve sustainable development in its three dimensions — economic, social and environmental — in a balanced way. While the agenda itself is global, it takes different national realities into consideration and guides and permits governments to incorporate these goals and targets into their national planning processes and strategies as per their priorities.

The 2030 Agenda, while defining its goals and targets as aspirational and global, recognized the significance and the need to leverage a wide range of data , including earth observation and geospatial data , for the follow-up and review of the progress made in implementing the goals and targets. The basic objective of the 2030 Agenda — that no one is to be left behind — will require quality, accessible, timely and reliable disaggregated data to help with the measurement of the progress. However, the Agenda acknowledges that baseline data for several of the targets remains unavailable and calls for increased support for strengthening data collection and capacity development in Member States, to develop national and global baselines where they do not yet exist.

The Agenda committed itself to conducting regular and inclusive reviews of progress at sub- national , national , regional and global levels. It encourages nations to identify and create most suitable mechanisms to build on existing follow-up and review mechanisms at these levels.

Earth observation and geospatial data supports measuring and monitoring of several, if not all, goals and targets set by the 2030 Agenda.

Geospatial professionals, for many years, both individually and collectively, have articulated and stressed the role, need and value of geospatial information, technology and services to the governments and decision makers. However, According to Greg Scott, Inter-Regional Advisor at UN-GGIM and Prof. Abbas Rajabifard, Head of Department of Infrastructure Engineering , University of Melbourne, “Now is the moment in time where we can, and must, elevate and demonstrate our ‘geospatial value proposition’. The global geospatial community , particularly through national geospatial information agencies, has a unique opportunity to integrate geospatial information into the global development agenda in a more holistic and sustainable manner, specifically in measuring and monitoring the targets and indicators of the SDGs.”

However, the opportunity brings with it substantial expectation to deliver. This is not an easy task as very little is understood regarding the role of geography in sustainable development processes at the inter-governmental level, including how geospatial information can be applied to sustainable development, and how policies can be implemented to bring the two together in a coherent and integrated manner. However, a few common threads could be identified that could potentially be useful for furthering the SDG Agenda.

The 2030 Agenda demands the need for new data acquisition and integration approaches to improve the availability, quality, timeliness and disaggregation of data . While the indicators are extremely ambitious and it is not clear exactly what data is needed and if that data is available, experts opine that it is important to exploit the data that already exists. “A major part of the data gap in many developing countries is in fact a discovery gap. Bridging providers and their data with facilitating mechanisms to increase discovery and usage is key,” says Simonetta Di Pillo, Director, United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs (UNOOSA).

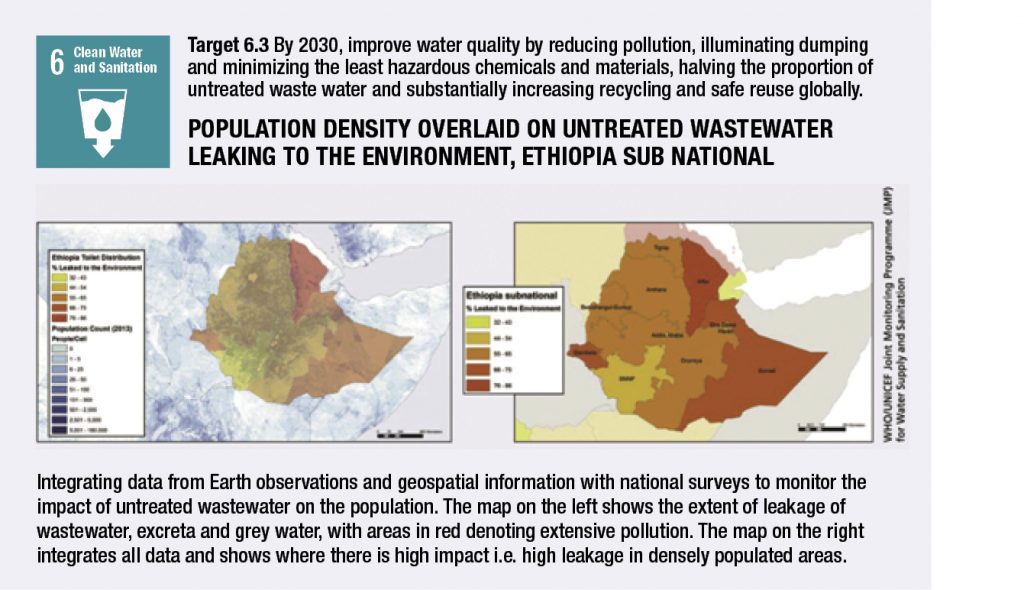

However, Rifat Khondkar Hossain, who is the focal point for MDG /SDG water and sanitation indicators at the World Health Organization , differs. “I don’t think data is sparse, more so because EO data is available for development monitoring,” he says. “If you look at a country, certain parts of the country may be data poor but the country as a whole, rather almost any country in the world, is quite data rich. We just have to make countries aware of the availability of data and create bridges between data poor and data rich paradigms.”

As geospatial community works through the targets and indicators of the SDG Agenda, it is realizing that significant data gaps exist, not so much in their spatial resolution but in their temporal resolution . Also, in several cases, data is available but needs to be repurposed for new needs. “That creates, to a degree, a challenge for the professional community . To be able to do this, we need to partner a lot more with international organizations and private sector who often have a more responsive ability to bring, particularly EO data , to the discussion rather than some of the traditional means we have,” stresses Scott.

Having data is one thing, having high-quality data is another thing. For example in Europe , stakeholders are focusing on geospatial standardization and increasing the richness of data , while several remote pockets of Africa are facing data scarcity.

The heightened importance of data and its availability for measuring and monitoring SDG progress increased momentum around the discussion to open up data . Successful examples point to a large number of areas where open government data is creating value, increasing transparency and democratic control, facilitating new products and services, improving efficiency and effectiveness of services, improving innovation and empowerment, creating new knowledge from combined data sources and patterns in large data volumes. For example, Danish investment of $125 million in spatial data infrastructure between 2012 and 2016 brought returns of an estimated $33 million net benefit per annum for the public sector and $66 million net benefit per annum for the private sector .

The Group on Earth Observations (GEO), which is spearheading EO data availability for societal benefits, is championing the cause of open data . Barbara Ryan , Director, GEO Secretariat, says, “Whether it is from space, from the atmosphere, from the marine environment or from the land, if public resources and taxpayers’ money went into building the satellites and/or the instrumentation, then the data needs to be released broadly and openly. Governments should not be charging their citizens for data that they have already paid for.”

Scott adds, “To have good interoperability , to have good data and information systems, having free and open access to not only relevant data but timely data that is maintained and sustained will be of continuing importance as the SDG Agenda has a 15-year time-frame (till 2030).”

The buy-in of a broad range of stakeholders is key for the success of Agenda 2030 and open data and democratization of access to data and information plays a key role in gaining stakeholder-acceptance. Adding another dimension to the debate, Stefen Jensen, Head of Data Management Group, European Environmental Agency says, “When I look at the indicators under the sustainable development goals and targets, some of them are extremely ambitious and it is not clear exactly what data are needed and if that data is available. This area requires lot of clarity and open data can play an enabling role in this.”

While availability of data is fundamental for SDG implementing and monitoring, experts think it is not sufficient. “The decision makers on SDG implementation are normally far away from data on the value chain from EOs to end users and more interested in information and knowledge than just data . We need to focus on the transition from data to information to knowledge and create tools that provide access to knowledge. In this process, it is important that these tools are co-designed with end users,” feels Shelley-Ann Jules-Plag and Hans-Peter Plag, Old Dominion University, Norfolk, VA, USA. Currently, most of the data delivery, information and knowledge systems have a push component to push out what providers created, while a pull component to get the knowledge created when needed does not exist. If we truly want to support both implementation and monitoring of SDGs, the pull component needs to be developed in a co-design and co-creation process, the Plag duo add.

To enable this, Hossain believes that a clear dialogue between data providers and the data users is necessary. “GEO has to take the SDGs seriously and it can in fact become its mantra. The EO community has a humongous opportunity to use the SDG framework as a driver because there is a lot of demand-supply gap and they often do not speak the same language. The data and solution providers need to reach out to the user communities , understand their specific needs and how they can cater to those needs,” he adds.

Significant technology innovation and intellectual capacities are being developed within the private sector often either do not percolate or see delayed adoption by government entities leading sustainable development activities. Considering that geospatial technology and application is taking-off rapidly in private space with cost-effective innovations in sensors and software, small satellites and drones supported by advancements in IT and data analytics, it is prudent to make private industry an equal stakeholder and partner in evolving regulations and in implementing projects pertaining to SDGs.

Several frameworks already exist at global level either facilitating data access and/or providing advisories to nations in creating frameworks and infrastructure for facilitating geospatial information. The United Nations ’ initiative on Global Geospatial Information Management (UN-GGIM) is working closely with the statistical community , at national and global levels, to provide inputs into the processes to develop the global indicator framework with the IAEG-SDGs.

GEO is committed to create a Global Earth Observation System of Systems ( GEOSS ) and promote the use of earth observation resources across multiple societal benefit areas and make those resources available for informed decision-making. GEO initiative GI-18 envisions the organization and realization of the potential of earth observations to advance the 2030. The initiative aims to enable countries and organisations to leverage earth observations to support the implementation, planning , monitoring, reporting and evaluation of the Sustainable Development Goals and their normative societal benefits. Further, GEO launched an initiative to expand its partnership with UN -GGIM to build processes, mechanisms and capacity to integrate earth observations with geospatial and statistical information to improve the measuring, monitoring and achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals.

“GEO has sufficient involvement of the S&T community to also support the implementation of the SDGs. An important task for GEO is to establish a working relationship with the Inter-Agency Expert Group-SDG (IAEG-SDG) to participate in the review of the current monitoring framework. The GEO Work Programme gets more visibly organized around the SDGs, and that we have more GEO Initiatives and GEO Community Activities related to the SDGs,” aver the Plags.

Scott points out at the need to integrate information systems at the national level. “The 230 indicators under the 17 goals will be used in different ways by different countries. So, that framework on how they use their data construct will very much depend on what institutional and architectural arrangements that already exist. In developed countries, that’s quite an easy consideration in terms of how they may modify a national spatial data infrastructure.” But that is not the case with developing countries , small island developing states and some of the least developed countries, where such infrastructures do not exist. This mandate, hopefully, will provide these countries an opportunity to start building and harnessing the processes. The institutional arrangements or the governance that goes around those processes and frameworks are starting to be created in developing countries , and that is within the scope of UN-GGIM.

Considering that the availability of core geospatial data is a pre-requisite for calculating the SDG indicators, there is also a need to build a consensus on the need to integrate the NSDIs into the national government’s development plans. An NSDI strategy that is anchored to sustainable development , as an overarching theme, would provide an ‘information’ approach to national policy and implementation. It would also bring the analysis and evidence-base to the process, and thereby a consistent monitoring and reporting framework, that would benefit all areas of government.

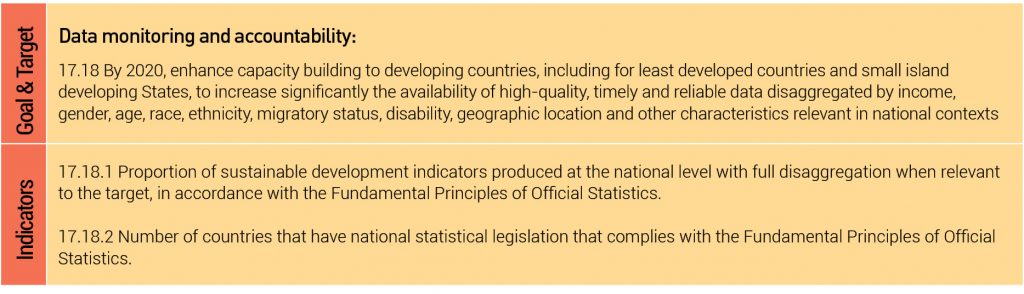

The monitoring of MDGs taught us that data are an indispensable element of Sustainable Development Agenda. Despite improvement, critical data , especially geospatial data , for development policymaking are still inadequate. Understanding that quality, accessible, timely and reliable disaggregated data will be needed for the success of SDG Agenda, the United Nations agreed to intensify efforts to strengthen statistical capacities in developing countries and least developed countries. Goal 17 explicitly discussed the need to strengthen the means of implementation and revitalize the global partnership for sustainable development (Table 2).

Experts feel that the biggest challenge for the 2030 Agenda is around capacity development and knowledge transfer and how they can take enabling technologies and capabilities from data – rich countries to data -poor countries. The UN-GGIM along with the whole UN system is conscious about capacity development. GEO’s GI-18 is strongly focusing on the development of training and capacity building programs directly related to the use of EO for the monitoring of Sustainable Development Goals.

The UN-SPIDER allocates financial and human resources to capacity building and institutional strengthening in a wide range of thematic areas, including the use of space -based technology and applications for disaster management , environmental monitoring, climate change , and global health . “UNOOSA assists the COPUOS, which has 83 Member States, to coordinate its actions in support of the 2030 Agenda. These actions aim to further bring the benefits of space technology and applications to nations implementing the 2030 Agenda. UNISPACE+50 is actually prioritizing building the capacities of nations in accessing and using space -based technology and applications for better planning and monitoring of SDGs at the national, regional and global levels,” says Pippo.

While a lot of training and capacity building efforts are going on globally, challenges remain to make sure that they are just not one-off events but are sustainable and that true capacity is getting built in countries. “To be able to ensure this, GEO is downscaling what it is doing globally to the regional level. The AmeriGEOSS, AfriGEOSS and HimalayanGEOSS initiatives bring respective governments and participating organizations together to integrate their capacity building efforts and training opportunities,” informs Ryan.

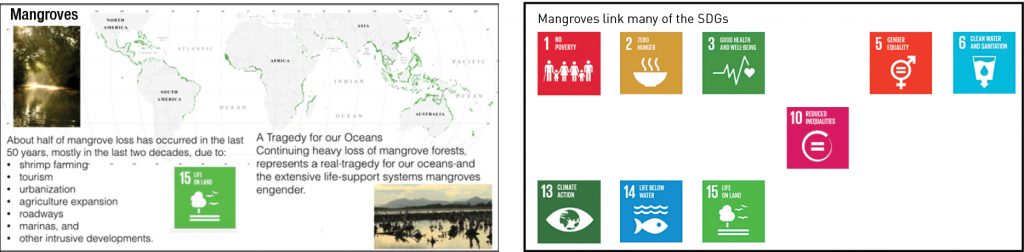

An important aspect of the SDGs that is often overlooked is the interdependency of the SDGs. Many of the individual SDGs depend on actions focusing on other SDGs, and capacity building needs to take this into account. “For example, restoring ecosystems under several Targets of SDG 15 may be in conflict with SDG1 and SDG2. The example of mangroves cited in Figure 2 (above) shows that they are connected to several SDGs,” say Plags.

What enables countries develop capacities are resources and it is common knowledge that resources are quite finite. The Addis Ababa Agenda provided a broad framework for the international community to finance sustainable development . Financing the Sustainable Development Goals will require at least $1.5 trillion extra annually over what was required for the MDGs ($120 billion annually). With respect to satellite -based EO imagery, one estimate puts the investment required at $150 million for start-up costs and $5 million in annual costs covering all 77 IDA countries.

The World Health Organization (WHO), which is spearheading the multi-agency efforts to create a SDG-wide water monitoring called Integrated Monitoring of Water and Sanitation for SDG targets (GEMI), is in discussions with data providers like NASA and JAXA . WHO intends to be an agent between these data providers and the users who are working on SDG water monitoring to facilitate the data uptake, format specifications and usage. Though several organizations are already facilitating or have initiated training and capacity development activities at global level, they are grossly under-adequate at national and sub- national levels. If these needs are not addressed suitably on a priority basis, they may severely hamper the implementation and progress of the Agenda 2030.

Data , especially geospatial data , is the basis for evidence-based decision-making, monitoring and accountability. The geospatial community recognizes that location and geography are significantly linked to many, if not all, elements of Sustainable Development Goals. The task before the world geospatial community now is to push the ‘geospatial value proposition’ envelope to the governments and decision-makers at every level.

The first progress report on Sustainable Development Goals released recently acknowledged that several national statistical systems across the globe face serious challenges with respect to availability of good quality, disaggregated data . As a result, accurate and timely information about certain aspects of people’s lives are unknown, numerous groups and individuals remain invisible, and many development challenges are still poorly understood.

In this background, the success of Agenda 2030 hinges heavily on the vision, motivation and commitment of the decision-making fraternity. It also depends on a close interaction between those who are in positions to make policies in support of the Agenda 2030 and decisions on actions for the implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals with those who provide the knowledge about progress towards the SDG targets and the impacts of policies and actions. Methodologies and infrastructure are needed to facilitate a co-design of the research agenda and a co-creation of the knowledge for the implementation and monitoring of the Sustainable Development Goals. To achieve this, it is important to sensitize and encourage local political centers and senior administrators to ‘own’ and ‘lead’ the geospatial efforts in their respective countries. Without their involvement much of the data and information derived will remain in the ivory tower of ‘ space research’.

Bhanu Rekha

Managing Editor Geobuiz